Ron's Tale

"What day is it?"

"It's today," squeaked Piglet.

"My favorite day," said Pooh.

- A.A. Milne

If you would like to listen to the audiofragment with English subtitels, click on this Youtube-link.

(Google translation) The opening question of the interview: "How do you experience this period, Ron, and by that we mean as a teacher of course, not privately?",

is answered with a counter question: "Is there a difference?".

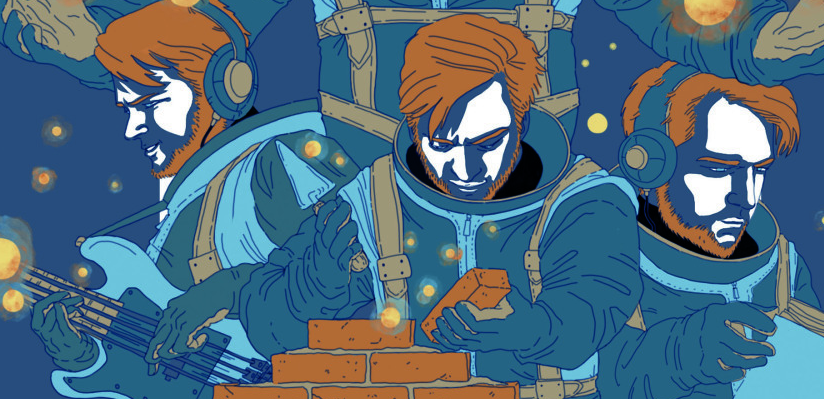

Ron takes us from the first to the last word in a whirlwind of teaching thinking. He teaches at the Teacher Training in Higher Education and is also completing the Master's degree in Art Education at Tilburg University. In the meantime, he also remodels his entire house himself, makes music, builds a studio in the garden for that purpose, listens to one podcast after another and in between reads the recently published book by Lieven Scheire. He speaks as he lives, passionate and hard-spoken. We start with a consideration in which he follows educational expert Gert Biesta: ”I have been very busy with the question of what education should serve. For me, in a sense, that's 'becoming human', getting signs about who you are as a human being and 'getting fodder' to develop that. I have the feeling that the so-called soft subjects, the humanities and the arts, are very important for becoming human. We live in a society in which a lot is measured: how many cars you have, what you have in your bank account, how big your house is. The hard subjects, which have an economic value, have become very important, while everything concerning the humanities or arts is just being swept away. Because they do not aim to achieve any result in themselves. And then we're very quick to say that we're including the arts in our curriculum anyway so that kids can get creative. But that way you view creativity from a financial standpoint, as something that serves something else. Creativity is then there to start up innovative companies or to come up with specific solutions. You could also say that creativity is learning to look at the world, learning to notice certain things and do something with it.”

He enthusiastically refers us to the podcast The magic of listening by Klara in which music philosopher Thomas Serrien confirms that music gives you freedom, because it leads you away from yourself and makes you look at the world with an open mind. A little later he talks with equal enthusiasm about the importance of boredom, inspired by actor and theater maker Peter De Graef, who talks about his project Sitting in another podcast: “Peter de Graef was asked: what should we teach children? He replied that we should actually teach them to be bored. I also think that that is the source of creativity, of getting inspiration. I have the example in my head from when I was thirteen years old, waiting at the hairdresser. If I made an appointment with my hairdresser at 2 pm, it was my turn at 4:30 pm or so. Do you know that? Then I would sit there for two and a half hours, waiting for a chair. Nobody cared about me. I had the Nokia 3310 at the time, you were done with it quickly, and the booklets that were there were not interesting either. Then I sat there looking around. I'm a real bum, so I quickly grabbed a brush from a cart and went to see how the hairs were attached to it. Then I looked at the hair dryer: ah ok, that's attached to it and that to it, and there's the bolt. I can still tell you how that hairdryer was put together. I just took the time to look at something. I discussed this idea of boredom with students and I noticed that they actually need it a lot. I wanted to spend about twenty minutes on this, but in the end it took at least three quarters of an hour. Because they find that very recognizable. They view it from the perspective of their environment in which they are very busy with their mobile phone, with Instagram. They find it very difficult to tolerate that boredom. As if boredom is a sin. We must be busy. For example, if you say to someone, "I don't have much to do, I'm bored," it sounds like you're not being successful. I feel like we should always go in the red. If you're not going into the red, you're not doing a good job. When my parents ask what it's like, I say: 'Press it!'. And then my mom says, "That's good, young one. Good. Good thing it's busy. You're still young. Now you must be busy'. I think that's weird. I really hope we don't have to do that anymore after Corona. That we can see that it is actually not so important to be so busy all the time. Bored, look inside yourself, I hope we will do that more.”

He is so engrossed in his story that he loses the thread: “Repeat your question?”.

He then explains that as far as he is concerned, boredom does not exist at all. He thinks for a moment and creates clarity: “If you view boredom as 'I don't know what to do anymore and I can't do anything with this, I really want something different. I now wish I could do that. I now want to see others, I want other people around me'. Yes, then that will also affect your functioning. But if you switch off that wanting, you will be more concerned with what is happening now. Then you try to see the opportunities, look at the possibilities”.

The dynamic in the story about boredom is that of the entire interview. Ron speaks enthusiastically about an idea that intrigues him. He is completely absorbed in the train of thought, bounces back on new ideas or questions and starts spinning them again. It happens that - sometimes half an hour later - he says something that seems contradictory, which determines himself, hesitates for a moment, searches and then brings clarity again. For example, he starts the interview with the question whether there is a difference between himself as a person in his private life and his teaching. He doesn't feel that way himself, he says. Halfway through the conversation he makes a distinction between the two: “I think – how should I say that – I am Ron, as a whole. That's my identity. And only part of it is a teacher of that. I'm so tired of seeing teaching as a person's identity. Pfff. I find that so loaded. I still think it's really weird, after the eight or nine years that I've been teaching now, that they call me a 'teacher'.”

Later still, he links the two statements together with the remark: “I think I have a different image of a teacher than the social image.”

In the same way he deals with the question of the importance of curiosity and the will to share in teaching: “Curiosity is useful, but it is not inherent in the teacher. Is it then that you are a sharer of knowledge, or something?”

A little later: “Curiosity is essential for a teacher” and: “Sometimes I don't feel like disseminating knowledge at all”.

At the beginning of the conversation he says that the Master of Arts Education has given him freedom and later that it has just taken the freedom away from him to do the things he wants to do: his music, his relationship. It's not so much that he contradicts himself. It is as if he is tasting ideas as he explains them and in the speech itself seeks the balance or nuance that allows them to exist in the same time and space. With the same fervor with which he defends the ideas of freedom and passion in education, he is angered by what he thinks stands in the way of good education. “What also annoys me so much at the moment is the discussion about the exams in the media during this lockdown: oh, oh, oh, what are we going to do with the exams. Isn't school meant to teach people, to 'feed' people? Do we really have to be busy checking whether they have learned that or not? If they haven't learned anything, what should you check? Take the time you still have this school year to teach children something!”

Later in the conversation, he adds to that thought: “We live in a huge control society. But because of that control, the essence of education is completely lost. This control suppresses people's curiosity. I come from a high school where I felt the same way. I had no interest in learning at all. I was not interested in that because I had to do things against my liking: fill in terribly uninteresting things on terribly uninteresting papers - even supplement. I didn't have to think. And I think you just have to teach people to think more. That you need to have those conversations. Not: we are going to quickly fill in our workbook because the inspection… or: otherwise we have not seen all the subject matter.

(gets upset) Like you can check off material. Today that is on the program, tomorrow that, and then that: check, check, check. Ah, we've seen all our learning material. Look at this, oh boy, we're doing well. We assume they know it because we've seen it. How many students are there currently in secondary schools who are graduating and do not know anything about the subject matter of the third or fourth year? How weird is that really? I'm learning about physics right now. I had completely forgotten what protons, electrons and neutrons were, although that is super interesting and I am very eager to learn. How is that possible? I find that very strange.”

He says about the 'social image' of the teacher: “Friends of mine say: 'If I have to work for a teacher, then I know that.' How do you know that? Because they often know better. Because they ask certain questions to check. I think I'm more interested in teachers who ask questions out of curiosity. Not for control.”

That image certainly does not fit with Ron himself: “If four cyclists have stopped to chat with each other, and it is doubtful whether they are six feet apart or not, then I am not the person to say: ' Wouldn't you even stand one and a half meters apart?' No, I don't feel the need to teach at all. New. That those people draw their plan, really.”

He is also excited about guiding students with their lesson preparations: “What really just always frustrates me is the endless discussion about making lesson preparations: should this be in the column of 'content' or in the column of 'approach'? Gosh… That's just form for me. I don't even want to spend time on that. That's not what teaching is about. It is indeed about determining that content. But where that should be in a 'column meke'... Students also indicate that: 'That's not your thing, is it?'. No, that's not my thing either! I want to talk about other things.”

Ron likes to play with ideas. Twice during the interview, those ideas suddenly take shape. Here they are no longer ideals in which it is pleasant to dwell, to defend fiercely or to jump from one interesting question they raise to the next. The thoughts come to life. The first time it happens when he tells about his father who taught him to grow. He connects the way his father, whom he describes as 'extremely skilled', teaches him during that period with the image of the teacher who takes you on a journey until he becomes redundant himself. Just as his father always took him along in his thinking while working, adjusted the level of the jargon at most, and then suddenly had to realize at a certain moment that they were thinking as equals about how thick the beam should be above that one doorway. The second time it happens when we ask Ron for an example of the 'educational gesture', a concept he gets from Biesta and which relates to the teacher as the one who points to what is valuable or important. He tells about a lesson he gave three years ago that has stayed with him. “I always have the feeling when you want to talk about art…. Experiencing art - and for me that is with music - is a kind of feeling. That you're in full engagement, like that. Like, 'Yes! That's super cool! That's super cool!'. For some crazy, stupid reason I can't explain what it is. Suddenly - that certainly is dopamine - I experience a certain happiness. You have that with some music. I had that at Bon Iver's Creeks, for example. I thought that was such a wonderful work. When I teach, I like to show the frontstage, but also the backstage. What's behind that now? I wanted to pass that on to students. That was really stupid, wasn't it, just: 'Mannekes, I want to show you something that I think is super chic. I also want to tell you why that is the case.' That's about four minutes or so, hey, that that happened. I announced it first. In that first listen you see a lot of people look very strange. Creeks is quite an abstract work, because there is no rhythm in it and it sounds very digital, but then again it is not. And then I showed them on a keyboard and with the microphone how that works: 'Now if I sing and I push the do, my voice will sound on that do, at the same time. If I key in the mi and the do, those two notes will sound with the same words.' So I was showing them the backstage of that song. And then I said, "Now we're going to listen." Then you see them listening in a completely different way. You see them really listening. While at first they heard. There is a difference between hearing and listening. I like to do that. Make them listen consciously. The best compliment I've ever received about that is that three students who had taken the class came to me years later: 'Oh that was such a beautiful song!' You see that that has given them something. I know from one of those students that the following year he had the entire album in his playlist. He had it all with him, that moment. You see that in people. For some, it stays with: 'Okay, yes, nice'. But you can also see that something is falling. You can have a played 'Ooh'. But you can also say a sincere 'Ooh!' or "Hmm!" to have. Like: 'Hey, that's interesting!' You see a genuine amazement. I don't think every teacher could have done it that way. You have to have a certain passion for something. That's the educational gesture. I see that as a kind of gift: the gift of the song. I think I've done that the moment I give an explanation with devotion, showing that I really think so. 'I really mean this'. I think people notice that. For example, if I'm really bitten by something, I go all out for it. That's typical for me. Then you can't stop me either. Then there's a kind of - how should I say - kick in. I don't consider myself a very good storyteller, actually. But sometimes I'm saying something and then I know: this is it! Those are usually those moments when you can tell something with a certain passion. I think it's in there. If I have to situate it in that lesson, you have that first listen, and then it comes: 'Now I'm going to explain something to you, and from there you're going to listen again. And then you listen. Then you won't hear. Then you will listen.' There it is, between those two listening moments.” We ask how Ron prepares that lesson. "How do I do that? I don't think I prepared that very consciously. Maybe by gathering a lot of information? I'm such a noob. For example, if I've seen a certain series, I want to know everything about it. Then I'm going to look up, look up, look up. Yesterday the second season of Ozark, a series on Netflix, ended. Then I need to know about that. What is Ozark? Where is that? Who are those characters? Where does that story come from? Where do those actors come from? Is that cast actually from Missouri, where it's set? Does that actor have such a heavy accent in real life? That search will lead you to certain things. It was just the same at Bon Iver back then.” For a moment he takes a different path, about the influence Bon Iver has had on his music and about the question why some things can suddenly inspire you and others not. We bring him back to the preparation of his lesson: “That's that. That is it. Just look up. Find things. And at a certain moment I also thought: I have to show that drink to people. Where did I feel that bubbling? That was when I heard that song. And then I read a lot about that. In fact it is, I sometimes think. I don't need any additional preparation. I think that's where the story took place at that point. The first time I taught that lesson, it took longer than I anticipated. What have I done? Play the song first. Discussed the album cover. And then I told about Bon Iver, what is the background of their music and about Justin Vernon, the driving force behind the project. I hadn't prepared that. That came then, I just started telling that, it just walked. That Justin Vernon… You have to imagine, that's someone who had a lot of success with his first album on which he played folkie songs. So he could very easily, if you talk about money, continue his next album in the same tradition. Because he already has a certain fan base. And you know that by doing that electronically, you're addressing a very different fan base. That is also very interesting. Someone who can really play for sure suddenly chooses: no, I won't, because he wants to set himself a challenge.” He muses further: “I think you have to be aware of something in the first place. I think my father has that too. At some point, something will happen. You can see in people's eyes that they are super interested. Or you just find it super interesting to tell us more about it. If you know what you're talking about, it will come naturally. If you have no substance and then you start to say something, it remains just a speech: I have prepared something and I only know this about it, what is written here on my paper. You can also see this with Lieven Scheire, for example. That dude never got his degree in Physics at the University of Ghent, because he then went on tour with the Side Effects. But you can see that he totally is. He finds that super interesting, he knows a lot about it. When you see that man talking, he does so with a certain passion, an enthusiasm. Just like Bart Van Loo in his podcast the Burgundians. He knows a lot about that and is so passionate about that subject that he can bring it in a tasty way. I think you have to have that, that enthusiasm.” Ron gave the lesson on Bon Iver a few more times. At some point he noticed that she was losing strength. “You do feel that. From the moment you're telling something and you know, because it's the umpteenth time you do it: then that comes, and then that… Then it's gone. Then it's gone. Then the inspiration is gone. Because you're just rattling it. I also know: this has not arrived. And then I stop. I still try sometimes. Because I think: God damn it, it was in there. It's in it. But it won't happen anymore. And then I think: come on, I'm going to try something different. This year I taught Peter Gabriel's Solsbury Hill.” This leads him to the next question: “My most powerful moments as a teacher, I have always felt, are the moments when I step off pre-conceived paths. Destination unknown... When do you play with spontaneity in your profession?” We are curious which podcast, which book, which idea, which thinker will put him in the starting blocks this time. Unfortunately, an internet connection problem puts an abrupt end to it. A little disappointed we clap to our computers. At the same time, we ask ourselves: what if the internet hadn't given up? Would Ron ever stop on his own?